By: Sarina Trangle (Business Reporter at Newsday)

sarina.trangle@newsday.com; Twitter: @SarinaTrangle

Updated June 16, 2023 2:37 pm

Link to original article: Click here to view

All photos contained below: Credit: Newsday

Long Islanders who hustled to get certified to sell recreational cannabis say localities are treating the state-awarded credential as a license to shun their business.

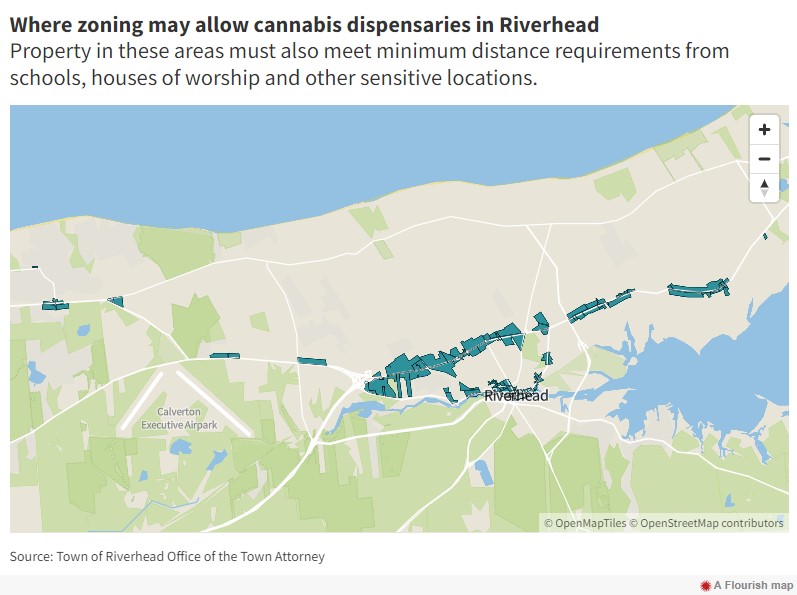

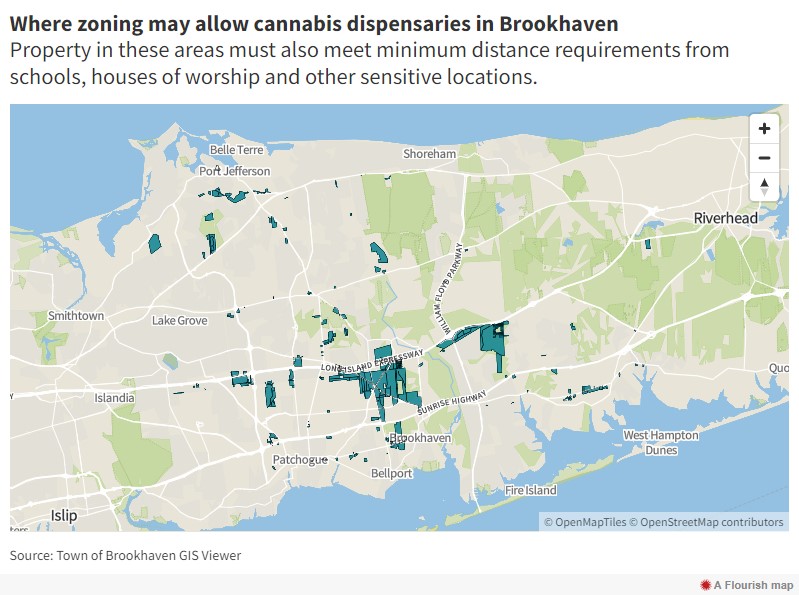

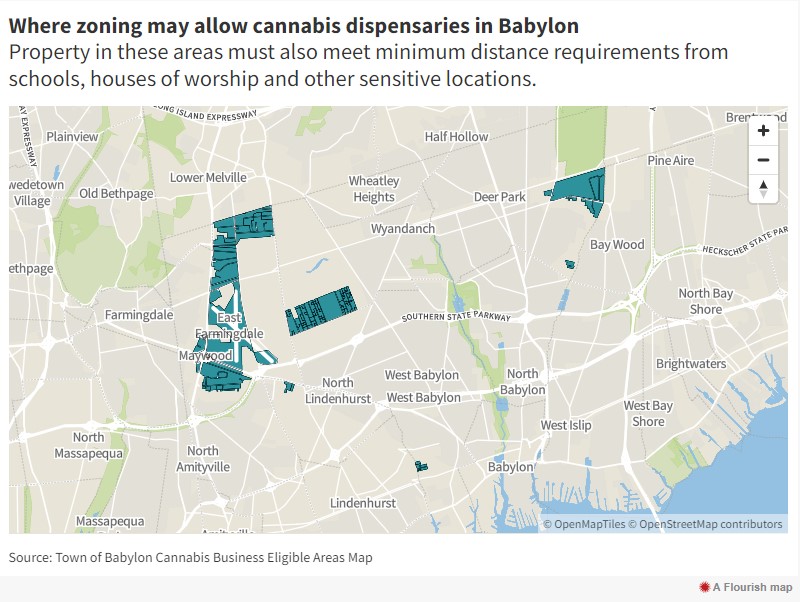

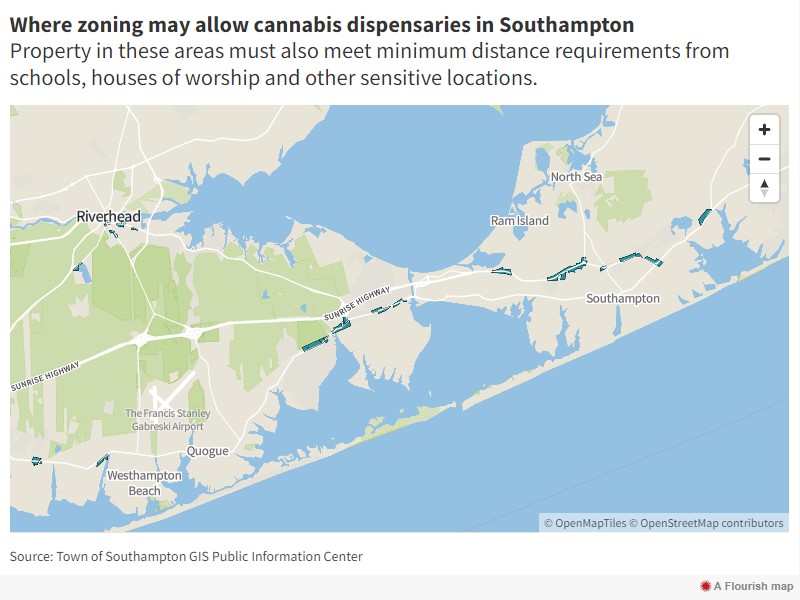

They say they’re scouring a largely unwelcoming landscape: Just four of 13 towns on the Island are allowing cannabis shops: Babylon, Brookhaven, Southampton and Riverhead. Within these towns, dispensaries are largely limited to industrial areas and select retail quarters. In Riverhead, for instance, just one or two buildings comply with all the local regulations, according to a dozen conditional licensees involved with the Long Island Cannabis Coalition, a trade group.

Many of the licensees involved with the coalition have the means to start a dispensary without tapping into a state-affiliated social equity fund, said Hugosbely Rivas Jr., who helped start the trade group.

Still, securing storefronts remains a challenge and businesses must meet deadlines. They may technically lose their license if they don’t open within a year, although regulators have indicated the state will be flexible on that front, according to Brian Stark, who in November was one of the first Long Islanders to receive a license. The coalition hopes to prevent that by educating Long Islanders about how the legal industry is regulated and monitored, convincing more towns to allow dispensaries and urging officials to crack down on unauthorized weed businesses.

So far, just two of 39 licensees have announced a location, and one of those still requires the town’s approval. Although industry regulations proposed by the state may provide relief, there aren’t enough eligible properties for all of the licensees to set up shop, let alone others who aspire to enter the field, the coalition said.

The state has so far issued only temporary or “conditional” dispensary licenses. These are restricted to New Yorkers who have run profitable businesses and have — or are related to someone who has — a marijuana-related conviction. Licenses will later be opened up to others.

“Everybody is still looking at us like we’re felons,” said Stark, a Merrick resident who plans to brand his firm Metropolis Cannabis. “If we were these so-called felons, we’d all be opening up illegal shops. We’re instead trying to do the right thing for our community, for our kids.”

Riverhead officials believe less than 30 shops could open in the locality, Town Attorney Erik Howard said. The other three towns declined to provide estimates of how many shops could open within their boundaries under current guidelines.

Distancing dispensaries in Riverhead

Riverhead has enacted several restrictions for dispensaries: They must be 1,000 feet from the property line of housing, schools, libraries or day cares; 500 feet from town beaches, playgrounds, community centers or houses of worship and 2,500 feet apart. Stark says he’s only found one property near the Tanger Outlets that meets the town’s criteria. The space is larger and more expensive than most licensees are looking for, he added.

“There’s one — maybe two locations,” that meet zoning requirements, said Riverhead Town Board Councilman Bob Kern, a liaison to the Business Advisory Committee, which has urged the locality to relax its rules. “People are looking, but they’re going to be hard-pressed to find something.”

Town Attorney Howard offered a different assessment, saying roughly 30 properties meet all the guidelines. But some of these properties will cease being eligible as shops open because of the required distance between outlets. Howard isn’t aware of any formal dispensary applications and said the town doesn’t have a record of multiple licensees struggling to find a location. He said it wouldn’t be wise to alter the months-old zoning until the town has more data on the rules.

“Once the code is in place, it’s still up to property owners if they’re gong to pursue that type of use or lease to someone who wants that type of use,” Howard said. “Those are some of the problems that you really can’t draft code based on.”

Storefronts that meet town standards are also rare in Brookhaven, according to licensees. They’re relegated to light industrial zones that are at least 500 feet from a property that could, potentially, become housing, according to zoning code.

Town spokesman Jack Krieger didn’t respond when asked to estimate how many stores could potentially open in these areas, given that dispensaries will need to be a mile apart.

At least three applications have been filed in Brookhaven, the coalition said. But entrepreneurs eyeing the area say they’ve hit a wall.

Weed licensee zoned out in Patchogue

Within about six weeks of getting a conditional license, Albert Capraro confirmed that a property he owns in Patchogue meets the state’s standards for a dispensary, according to an email he showed Newsday from the State Office of Cannabis Management. Brookhaven shot down the location about two months later, according to Capraro, a lifelong resident of the town.

The property, 488A E. Main St., borders a light industrial area along the LIRR, but was rezoned to allow for retail uses about a decade ago. Capraro, of East Moriches, said he wasn’t given the correct zoning from the prior owner. Town officials noted the site is in an area that’s historically housed retailers.

Capraro would like to open a dispensary, Grass Express, in his hometown. He has presented about 25 locations to Brookhaven planning and building department staff, but said none met the town’s criteria. In one case, space at 476 Long Island Expressway S. Service Rd. in Medford was ineligible because it was near a section of the LIRR, where zoning would allow future residences, according to Capraro. He said adding housing nearly 30 feet from the tracks wasn’t realistic.

Capraro estimates he has put $100,000 toward opening a dispensary and spent months hunting for space at the expense of attending to his business, Glass Express, which repairs windows, partitions and storefronts.

“It’s hard,” he said. “It’s hard to live on Long Island … Taxes are a lot; electric is a lot; heat is a lot; everything is a lot.”

Krieger said the town can’t ignore zoning code because of “the probability of the property being developed according to its zoning.”

“In instances such as that, there are administrative processes that enable land owners and developers to seek relief from the requirements of the code and property owners and prospective tenants are encouraged to seek advice from a land-use attorney,” Krieger wrote in an email.

Babylon map bars pot shop clusters

Babylon also limits dispensaries to industrial areas, but has attracted more attention from licensees because of its upfront approach. The town published a map showing industrial zones that are an appropriate distance from residential areas, along with a list of the roughly 850 lots they contain. But licensees must still verify identified locations are far enough away from houses of worship, schools and other sensitive locations.

Once shops open, others will be barred within a 500-foot radius — which may mean people looking nearby are suddenly disqualified, Stark said.

“People were literally getting LOIs” or letters of intent to lease “anything they could,” which made licensees worry that their negotiations would be rendered moot when others signed leases nearby, Stark said.

Babylon doesn’t have an estimate on how many dispensaries could open under its guidelines, according to Matt McDonough, an attorney for the town. So far, one dispensary, Strain Stars, has announced a location in Farmingdale. State officials said Budding Industry Group is slated to open a dispensary in Deer Park within weeks, but the company has not yet applied for a review by the town’s planning department.

Claims that the town’s zoning is overly restrictive are misplaced, McDonough said in an email.

“Often it is the landlord (free market) not the town (regulator) who is unwilling to rent,” McDonough said.

Southampton has taken a less restrictive approach, but conditional licensees say they’re wary of trying to compete with businesses on the Shinnecock reservation. Consumers won’t have to pay taxes as high when buying from stores licensed by the Shinnecock Nation, and tribal businesses will be able to advertise in ways New York State forbids.

Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman said his community hasn’t received a dispensary application yet.

“There are plenty of available properties,” Schneiderman said. “It’s really up to people to figure it out.”

What state is selling

Licensees, however, are looking to the state, which is trying to drum up municipal support for a “legal and accessible adult-use cannabis market” on the Island, according to Trivette Knowles, a spokesperson for the state Office of Cannabis Management.

“The State is working with municipalities across Long Island to help them understand the economic benefits of legalization and the urgent need to support the licensed stores that provide safe and tested cannabis products instead of the unregulated businesses that endanger public health,” Knowles said in a statement.

State regulators have proposed regulations that, if approved, would prevent localities from adopting stricter location rules than those set forth by the state. Complaints could be brought before the state Cannabis Control Board, which would issue an advisory opinion on whether the local rules are “unreasonably impracticable.”

The advisory opinion would signal to localities that their rules go too far, according to Sean McGowan, partner at Kaufman McGowan PLLC, a law firm that represents cannabis companies. But licensees may have to head to court to get localities to abide by advisory opinions, he said.

“They’re going to have to get an advisory opinion from the [Cannabis Control Board], and then hopefully at that point, the municipality plays ball,” McGowan said. “If they don’t, now you’re talking … lawsuits.”

Efforts by the state to overrule local zoning would not be welcome in Riverhead, said Howard, the town attorney. Residents and leaders dedicated multiple meetings to discussing and developing the zoning rules, Howard said.

“It almost undermines the whole structure that they [the state] put in place, initially, which allowed municipalities to opt out, or you could opt in with the understanding that we would have the ability to do time, place and manner regulations,” he said. “This would be sort of a bait-and-switch.”

The regulations proposed by the state may also pave the way for medical marijuana companies — many of which are publicly traded — to start serving recreational customers in one of their medical locations. But the medical dispensaries on Long Island may not be able to quickly make such a transition since their shops don’t appear to meet local zoning rules for recreational shops.

Many of the conditional retail licensees are anxious about potentially competing with the medical companies, many of which have operations in multiple states.

“The advantage of time is slipping away,” said Gahrey Ovalle, who received a conditional license with his brother. “We were supposed to be able to start here early and grow roots … so that we’re strong enough to endure the entrance of these larger operators.”

With Denise Bonilla, Carl MacGowan, Tara Smith, Joe Werkmeister, Mark Harrington and Arielle Martinez